The terraced house was the norm for new homes during the late nineteenth century up to the First World War (see previous post), but thereafter it was the semi-detached house that emerged as the standard format for council-housing and private developer/builders alike. And as I have explained, despite the Tudor Walters Report’s promotion of the wide-fronted house (for reasons of ventilation and sunlight) the ‘front’ and ‘back’ rooms of the traditional terrace proved very enduring.

The semi-detached home was distanced from the down-market terrace by the gap between pairs of houses, an innovation that also had many practical advantages – giving access to the garden without the need for an alley to the rear and providing somewhere to store bins, bicycles and perhaps even a garage for a car. And its aspiring new owners weren’t about to do without a formal front room.

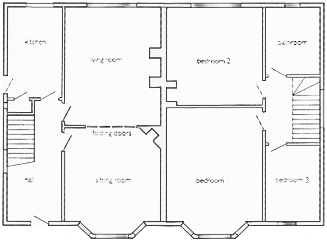

In his book ‘The English Semi-Detached House‘ (named with a nod to Stefan Muthesius’ classic work ‘The English Terraced House’, perhaps), Finn Jensen describes a ‘universal semi’ (right, above), the layout of which was almost ubiquitous, despite being dressed up in a number of different costumes – neo-Georgian, Arts and Crafts, Tudorbethan, even Moderne.

In his book ‘The English Semi-Detached House‘ (named with a nod to Stefan Muthesius’ classic work ‘The English Terraced House’, perhaps), Finn Jensen describes a ‘universal semi’ (right, above), the layout of which was almost ubiquitous, despite being dressed up in a number of different costumes – neo-Georgian, Arts and Crafts, Tudorbethan, even Moderne.

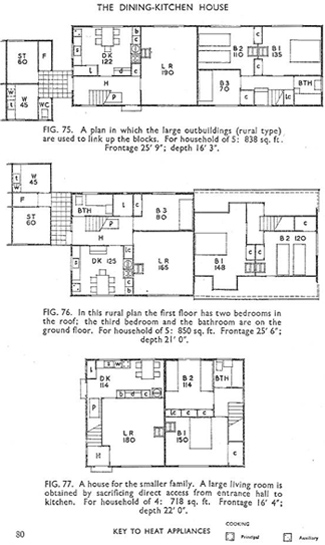

Given the prevalence of the universal semi by the end of the inter-war period, it is perhaps not surprising that in its briefings for a post-war house-building drive, the government again sought to stress the potential advantages of abandoning the formal ‘front room’ in favour of a single ‘through’ living room – just as the Tudor Walters Report had done twenty five years earlier. The 1944 Housing Manual included illustrations of a number of wide-fronted house-types (right, below).

Given the prevalence of the universal semi by the end of the inter-war period, it is perhaps not surprising that in its briefings for a post-war house-building drive, the government again sought to stress the potential advantages of abandoning the formal ‘front room’ in favour of a single ‘through’ living room – just as the Tudor Walters Report had done twenty five years earlier. The 1944 Housing Manual included illustrations of a number of wide-fronted house-types (right, below).

I wanted to mention this, because this was the context in which Tayler and Green began their work for Loddon District Council on the mid-1940s. But their adoption of the wide-fronted house is one of the things that makes Tayler and Green unusual; most modern architects were on a different trajectory….